How do politicians and/or citizens use digital technologies to engage in politics in a post-broadcast democracy?

Digital technologies have radically changed the communication dynamics between politicians and citizens. The post-broadcast democracy of high audience fragmentation and unpredictability is a result of time-shifting behaviour, adoption of personal devices, and increased media consumption options (Wilson, 2013). These digital technologies have transformed campaign strategies; enabling politicians to interact with journalists, engage in dialogue with constituents and craft a publically desirable image.

For the purposes of this blog, I will focus my attention on the Australian political environment, where the most profound changes in citizen-politician dynamic is a result of the social nature of new digital technologies.

The affordances of networked media culture enable citizens to engage with politicians in real-time two-way conversation. Politicians exist to represent the views of their electoral constituents, and so social media appeals to the very core of politics itself by allowing opening the lines of communication between constituents and their political representatives.

Australians have opportunities to engage with politicians through a number of social platforms, for example:

- Asking Kevin Rudd tricky questions in an AMA (ask me anything) on Reddit.com

- Hanging out with Stephen Conroy and Malcolm Turnbull in a Google + Hangout

- Participating in an economic debate with Craig Emerson on Twitter

These platforms provide citizens with an opportunity to voice their opinions, pose questions and contribute to the debate. On the subject of Twitter, Former Senior Minister Craig Emerson has said,

“You can contribute to the debate … it’s the equivalent of using Question Time around the clock.” (Craig Emerson, 2012)

In the near future, social platforms could even have the capability to influence public policy. Earlier this year, a Liberal voter frustrated with the Government-Elect’s broadband policy, created an online petition asking the government to reconsider its policy. The petition received over 270,500 signatures, with one signature provided every 3.5 seconds within the first week.

While this petition did not influence change to public policy, it prompted attention from national media and an official response from the Communications Minister, Malcolm Turnbull. In this regard, it successfully contributed to the political debate.

Internationally, online petitions have successfully altered public policy – for example, US political supporters of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and Protect IP Act (PIPA) backed down after an internet blackout and a 4.5 million strong petition. This exemplifies that digital technologies have the capability to influence public policy.

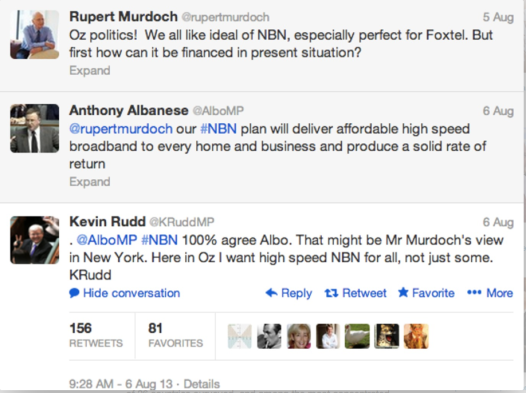

In addition to providing citizens with a voice, social media platforms provide politicians with an opportunity to discuss issues with journalists. For example, below is an online exchange between media magnate, Rupert Murdoch, and politicians Anthony Albanese and Kevin Rudd:

As audiences have moved online, so too have journalists for the purposes of reaching audiences, making contacts and receiving timely updates on news (Jericho, 2012). In The Rise of the Fifth Estate: social media and blogging in Australian politics, Greg Jericho explains,

“Twitter … turned the tables. Here was a medium in which news was being discussed, and where information was being relayed, in such a manner that, if journalists wanted to be across everything in their field, they needed to be onboard” (Jericho, 2012).

Much like politics, the journalism industry has also experienced a shift away from the homogenous audiences of the ‘broadcast audience’, to the fragmented audience of the ‘post-broadcast democracy’ (Wilson, 2013). Digital technologies enable users to receive information when they want it, and how they want it, which has created a user expectation that content should be online as soon as news breaks. In Australia, journalists such as Latika Bourke, ABC’s political and social media correspondent, frequently live-tweet quotes and announcements straight from the press gallery in Parliament House.

Whilst digital technologies allow journalists to quickly disseminate information, it also allows politicians to disseminate information directly to constituents without spin or bias added by journalists. As explained by Malcolm Turnbull,

“The attraction from any politician’s point of view . . . is that it means you can communicate directly without having to go through the gatekeepers in the mainstream media,” (Malcolm Turnbull, 2012)

It also allows politicians to use social media as a public relations tool to construct a favourable public image. Jason Wilson, author of Kevin Rudd, celebrity and audience democracy in Australia, explains:

“The role of party bureaucracies and members in election campaigns has declined as the tools of political marketing have become more prominent. Leaders have sought to communicate directly with voters using the electronic media” (Wilson, 2013).

As Wilson proclaims, in Australia, the best example of this is Kevin Rudd, who was known to be quite unpopular within his own party, but popular within the Australian public. Rudd’s popular public image gave him with an edge over his fellow party members, resulting in a leadership spill in his favour in mid-2013. Rudd’s success in this instance could be attributed to his ‘celebrity-like’ public persona, which was carefully constructed through a variety of media, including social media (Wilson, 2013).

Source: http://www.news.com.au

Rudd used social media to build a strong relationships with online audiences by sharing intimate details and a good sense of humour, to project a friendly, ‘Dorky Dad’ image. For example, here is Kevin Rudd’s humorous response to a question on Reddit.com:

And here is a video where Kevin Rudd discusses the rationale behind his infamous shaving selfie:

These examples demonstrate that digital technologies have forged a massive shift in political communication dynamics between politicians and citizens in Australia.

Bibliography

The above hyperlinks, and the following academic texts:

Jericho, G. (2012). The Rise of the Fifth Estate: social media and blogging in Australian politics. Brunswick, Victoria, Australia: Scribe Publications.

Wilson, J. (2013, June 17). Kevin Rudd, celebrity and audience democracy in Australia. Retrieved October 24, 2013, from Sage Publications: http://jou.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/06/13/1464884913488724

Grade: HD